The Language of Rust

What Video Games Taught Me About Environmental Storytelling

Why does Vintage Story bother to name ‘Limonite’? Why does Sea of Thieves distinguish verdigris from rust? Why does Red Dead 2 track environmental details when most players will never notice?

Because these developers are doing what museums do: preserving questions.

They’re betting that somewhere, a player will wonder: ‘Why is this different?’ And in that moment of curiosity, the world becomes deeper. More real. More worth caring about.

The Statue of Liberty took 20 years to turn green. Not all at once—in layers. First brown (Cuprite), then black (Tenorite), then blue-green (Brochantite, from coal smoke), then olive-green (Atacamite, from salt spray). By 1906, she was the color we know today.

Her patina is a chemical diary: ‘New York Harbor, 1886–1906, coal smoke + sea salt.’

Every oxide tells a story. Every mineral is a puzzle piece. This is what I do—I read rust like detectives read crime scenes. The color of an oxide, its crystal structure, its location on a specimen: these aren’t random details. They’re records of where something was, when it was there, and what was in the environment around it.

So when I started analyzing rust mechanics in 39 video games, I wasn’t looking for realism. I was looking for language. Because if rust records 20 years of industrial history on a statue, what stories could it tell in game worlds that span centuries?

The Museum Philosophy: Preserving Questions

At the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, we collect rust minerals even when we don’t know why yet. We have specimens of Akaganeite—that aggressive yellow-brown saltwater rust—sitting in drawers, waiting. We collected them because we knew: someday, someone will ask a question we haven’t thought of yet. Someday, this specific mineral from this specific shipwreck will answer it.

Museums don’t just preserve answers. We preserve questions.

This philosophy shapes everything we do. When we collect a Cuprite specimen from a copper deposit in Arizona, we’re documenting how deep weathering transforms minerals. When we preserve Malachite from historic mining districts, we’re recording rural carbonate formation. When we catalog Brochantite from urban roofing copper, we’re capturing the chemical signature of industrial pollution. Each specimen is a puzzle piece whose importance might not become clear for decades.

And that’s what fascinates me about game design. Developers make the same choice: What do we preserve? What do we simplify? What details do we keep, even if most players will never notice, because some player, someday, will ask the right question?

Reading the Records: 2.4 Billion Years of Rust

Before I talk about video games, I need to explain what rust actually is in the real world. Because rust isn’t just ‘brown stuff on old metal.’ It’s a library of at least 12 different minerals, each recording different environmental conditions.

2.4 billion years ago, Earth’s atmosphere filled with oxygen for the first time. We call it the Great Oxidation Event. It was catastrophic—oxygen was toxic to most life at the time. But it left a record: banded iron formations, layers of red hematite in ancient rock, marking the moment everything changed.

Rust is planetary memory.

Fast forward to today, and we can read rust like tree rings. Each mineral forms under specific conditions:

Lepidocrocite (bright orange) forms in high-oxygen environments with moisture. It’s fresh, active corrosion—the kind you see on a rusting toolbox left out in the rain.

Goethite (yellow-brown) is what most people think of as ‘old rust.’ It forms in humid conditions, especially in bogs and swamps. For thousands of years, people collected it as ‘bog iron’ to forge into tools before they had advanced mining.

Hematite (blood red) forms in dry, arid conditions. It’s stable, dense, and ancient. The red soil of Mars? Hematite. The patina on a 2,000-year-old Roman sword? Hematite.

Akaganeite (yellow-brown) is the villain of the maritime world. It only forms in the presence of chloride ions—saltwater. Unlike other rust, it traps chloride against the metal surface, causing deep pitting that eats through ship hulls faster than almost any other oxide.

Magnetite (blue-black) is special because it’s protective. Gun bluing, sword bluing, controlled oxidation—this is the oxide layer craftspeople intentionally create to stop further rusting.

And copper? Copper tells even more complex stories. Unlike iron rust, which progressively destroys metal, copper forms a passivating layer—a protective patina that seals the metal from further decay. This is why we find intact copper coins from Roman times but iron weapons from the same era are often unrecognizable.

Malachite (vivid green) forms in clean air with CO₂ and moisture—think rural environments, ancient statues exposed to weather but not pollution.

Brochantite (sage green) forms when sulfur dioxide is in the air—industrial pollution, coal smoke, acid rain. The Statue of Liberty’s current patina? Not Malachite. It’s Brochantite, recording a century of New York City’s industrial emissions.

Atacamite (bright emerald) forms in coastal environments where salt spray adds chloride ions to the mix. Because Lady Liberty sits in New York Harbor, her patina is actually a blend: Brochantite from urban pollution plus Atacamite from maritime exposure.

Each mineral is a geographic fingerprint. Show me the rust, and I can tell you: Was this in the desert or the swamp? Coastal or inland? Ancient or recent? High oxygen or buried underground? That’s the language of oxidation.

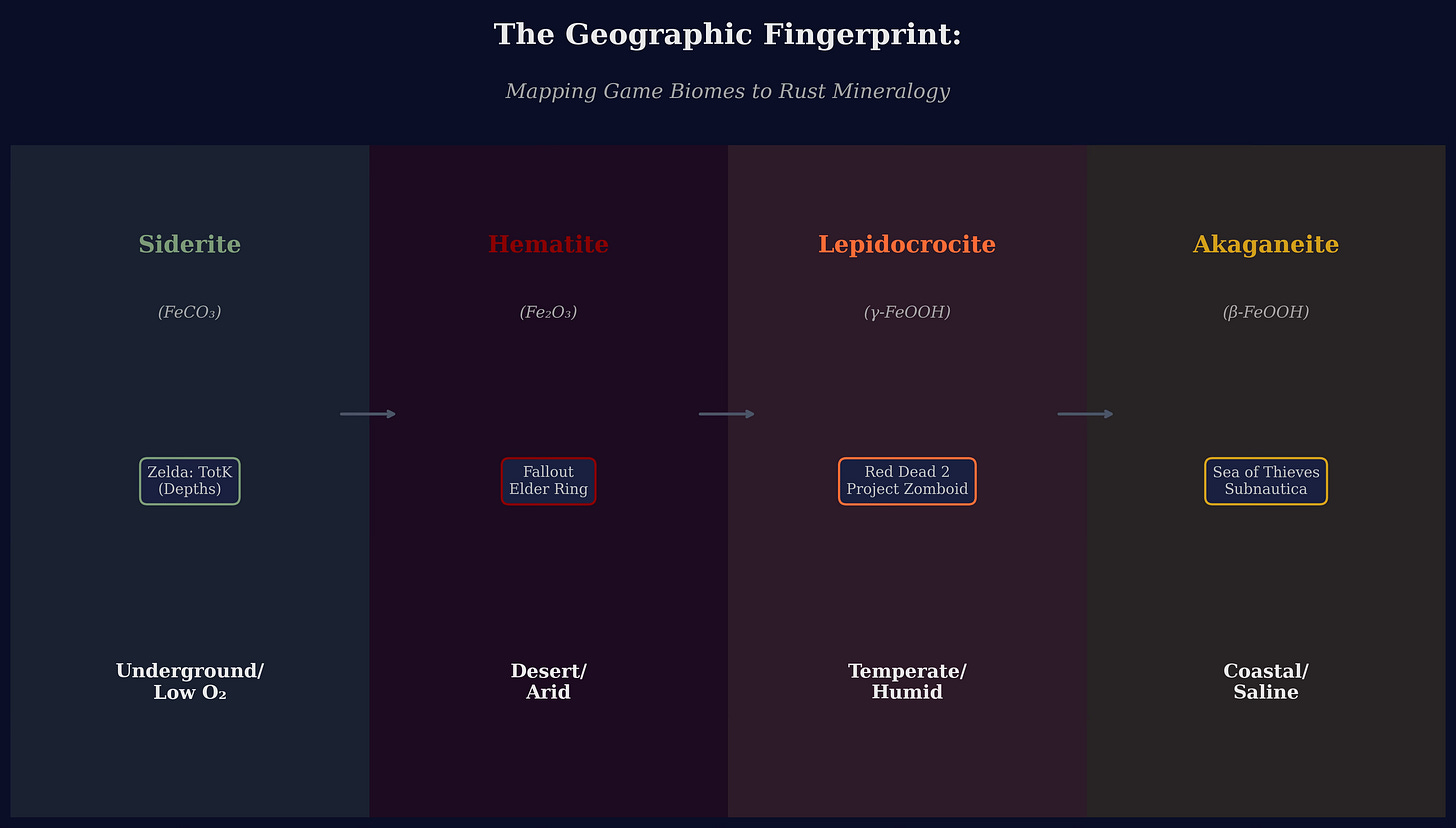

Mapping game biomes to rust mineralogy. Each environment corresponds to specific iron oxide or copper carbonate minerals formed under distinct atmospheric conditions. Game examples show how developers—knowingly or unknowingly—simulate real geochemical processes. Desert biomes favor stable Hematite (Fe₂O₃), while coastal environments produce aggressive Akaganeite (β-FeOOH) with characteristic chloride pitting.

The Discovery: 39 Games, 6 Design Categories, 4 Mathematical Models

When I started this project, I expected to write an article titled ‘Why Don’t Video Games Have Rust?’ I’d noticed that most survival games, RPGs, and simulations seemed to ignore metal decay entirely.

Then I actually started looking. And I found 39 games that do have rust mechanics—from massive AAA titles like Red Dead Redemption 2 and The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom to indie darlings like Vintage Story and Pacific Drive.

But here’s what shocked me: these games weren’t trying to simulate chemistry. They were simulating meaning. And they’d developed their own taxonomy—their own language of rust—that was entirely independent of mineralogy.

Six Design Categories

Through developer interviews, gameplay analysis, and design documentation, I identified six distinct ways games use rust:

1. Maintenance Simulation (Red Dead Redemption 2, Into the Radius, My Summer Car): Rust creates a maintenance loop. Neglect your tools, and they degrade. Clean and oil them, and they last. This isn’t about realism—it’s about creating a relationship between player and equipment.

2. Loot Archaeology (Zelda: Breath of the Wild/Tears of the Kingdom, Monster Hunter, Octopath Traveler II): Rusty weapons are progression gates. They look like trash but hide endgame power. The aesthetic of decay masks mechanical value—in BotW, Rock Octoroks can refine rusted weapons back to their true form.

3. Atmospheric Decay (Silent Hill, Fallout, Rain World, NieR: Automata): Rust is narrative vibe. It signals world history, abandonment, what game scholars call ‘mechanical melancholy.’ No stats change. The rust just means something.

4. Material Balance (Minecraft, Fortnite Save the World): Rust (or oxidation) affects building material properties. Copper turns green but doesn’t lose durability. It’s aesthetic progression without mechanical penalty—pure visual feedback for time passing.

5. Structural Integrity (Pacific Drive, Space Engineers, Subnautica, Project Zomboid): Rust creates ticking clocks on safe zones. Your base, your vehicle, your submarine—all corroding. The world itself is trying to reclaim your shelter.

6. Resource Economy (No Man’s Sky, Corrosion board game): Rust is raw material. You mine rusted metal, refine it, craft with it. Oxidation is just another step in the resource chain.

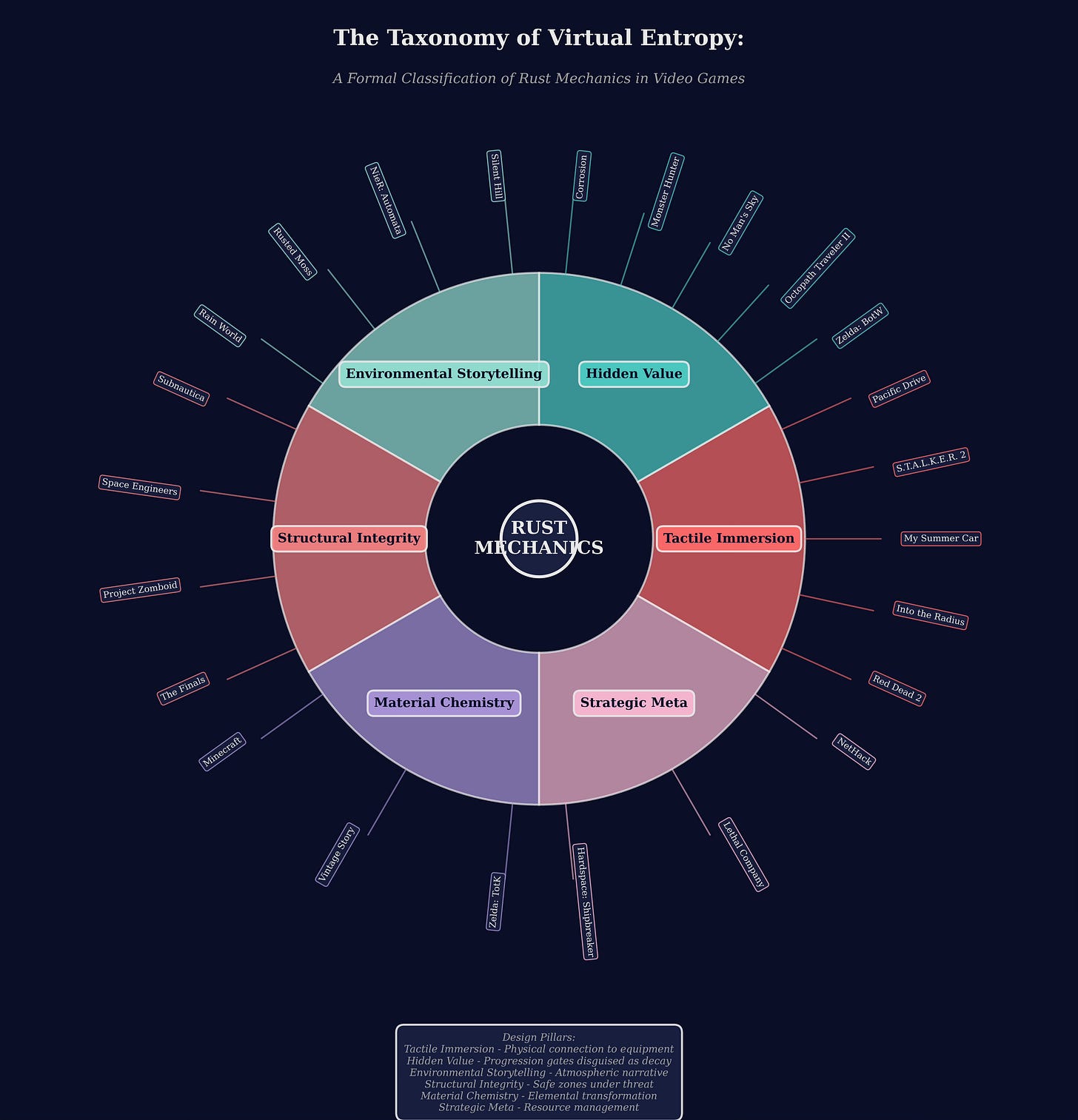

A classification of rust mechanics across 39 video games, organized by design pillar. This circular dendrogram treats game design choices as taxonomic categories analogous to biological classification. Tactile Immersion creates physical connection to equipment (Red Dead 2, Into the Radius). Hidden Value uses decay aesthetics to mask progression systems (Zelda, Octopath Traveler II). Environmental Storytelling employs rust as narrative atmosphere (Silent Hill, NieR: Automata). Each branch represents a distinct approach to simulating entropy in virtual worlds.

Four Mathematical Models

Even more fascinating: games have independently developed four distinct mathematical approaches to modeling decay.

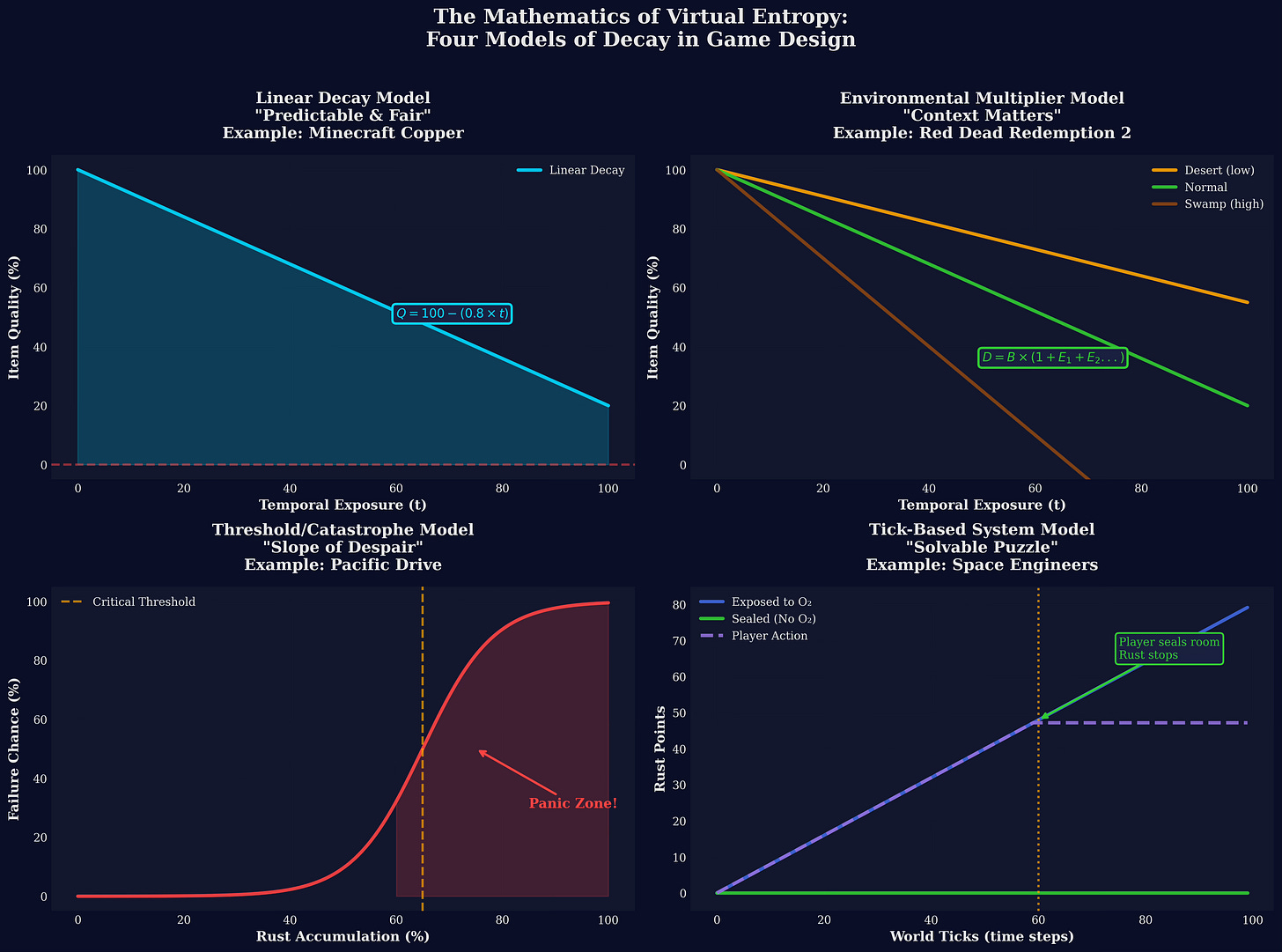

Linear Decay (24 games):

Steady, predictable decay. Minecraft’s copper oxidation uses this—it’s gentle, aesthetic, and actually chemically accurate for passivating layers.

Environmental Multiplier (10 games):

Base rate modified by location. Red Dead 2’s guns rust faster in swamps than deserts—and this is actually accurate to real humidity effects on corrosion rates.

Threshold/Catastrophe (4 games): Gradual buildup until critical point, then sudden failure. Pacific Drive’s system exemplifies this: car parts function relatively well as damage accumulates, but once they hit a critical wear threshold, failure is catastrophic—the part ceases to function entirely or develops a detrimental “quirk.” This matches real-world stress corrosion cracking, where structural integrity remains stable until a critical flaw propagates suddenly.

Tick-Based System (1 game): Space Engineers uses a modded system where rust is treated as binary: exposed to oxygen = rust accumulates, sealed = rust stops. It’s the simplest model, but it actually captures the core principle of atmospheric corrosion—controlling the environment controls the reaction.

Four distinct mathematical models games use to simulate decay. Linear models (Minecraft) provide predictable aesthetic progression. Environmental multipliers (Red Dead Redemption 2) adjust decay rates based on humidity, rainfall, and immersion—matching real corrosion kinetics. Threshold systems (Pacific Drive) simulate stress corrosion cracking with catastrophic failure. Tick-based models (Space Engineers) treat oxidation as a solvable engineering puzzle where player intervention stops the reaction.

Environmental Storytelling: When Rust Becomes a Detective Tool

When you encounter a rusted shipping container in a game, you’re engaging in the same deductive process I use in the field: environmental storytelling through mineralogical evidence. That yellow-brown crust isn’t arbitrary—it’s Akaganeite, and its presence is a confession that seawater was the culprit.

Game developers who understand this chemistry aren’t just adding texture detail; they’re deputizing you as a mineralogical detective, inviting you to reconstruct the narrative from physical evidence. Every rust color is a witness statement about what happened in that space.

Think about Silent Hill‘s rusted otherworld. The decay isn’t random atmospheric dressing—it signals psychological dissolution, the world breaking down at the seams. Or Fallout‘s selective rust: pre-war technology corrodes while certain vault-preserved items remain pristine, creating a visual timeline of the apocalypse.

The ubiquity of generic brown rust in games isn’t laziness—it’s efficient visual communication. Brown immediately reads as ‘old,’ ‘abandoned,’ ‘neglected’ across cultural contexts. It’s the visual equivalent of a minor chord in music: instant atmosphere.

What I’m offering isn’t a critique of this approach but an expansion of the palette. When developers want to distinguish between ‘abandoned for 20 years’ (stable Hematite) versus ‘rusting RIGHT NOW’ (aggressive Lepidocrocite orange), they have specific mineral pigments available. It’s not about replacing the shorthand—it’s about having specialized tools when the narrative demands precision.

The Chemistry of Reward: Magnetite as Gameplay

The Magnetite layer formed during gun maintenance in Red Dead Redemption 2 represents a beautiful convergence of chemistry and game design. When you successfully maintain your weapon, you’re not just preventing decay—you’re creating Fe₃O₄, a dense, protective oxide that actively slows further corrosion.

This black patina is both aesthetically distinctive (the deep finish of a well-maintained firearm) and functionally protective. The Magnetite layer has better adhesion and lower porosity than red rust, making it an actual barrier.

In gameplay terms, maintenance isn’t just halting a decay timer—it’s building armor for your weapon at the molecular level. The game rewards your diligence with good chemistry: proper care doesn’t just preserve; it restores. A well-maintained gun in RDR2 returns to peak performance, maintaining the optimal condition that environmental factors constantly threaten to degrade.

This is what makes the mechanic feel earned rather than mandatory. You’re not fighting entropy; you’re creating something protective, building up rather than just slowing down.

Minecraft’s Gateway Mineral: Teaching Chemistry to Millions

Minecraft’s copper weathering system may be the most significant science education event in gaming history. For millions of players—many encountering chemistry concepts for the first time—it demonstrated that color change represents transformation, not contamination.

The progression from orange metal to cyan carbonate isn’t decorative; it’s showing players that copper atoms are recombining with atmospheric gases to form entirely new minerals. By making this process reversible (scraping off patina) and controllable (waxing to preserve states), Minecraft turned basic coordination chemistry into an intuitive building mechanic.

It’s a gateway mineral: once players understand that copper ‘rusts’ differently than iron, they’ve grasped the fundamental principle that each element has unique chemical reactivity. They might not know the word ‘passivation,’ but they understand the concept—that some oxidation protects rather than destroys.

Minecraft is also notable for showing copper patina progression through distinct color stages rather than treating it as a binary state. Most games treat copper corrosion as simply shiny or green, but Minecraft preserves the intermediate oxidation states, teaching players that chemical change happens in stages, not instantaneously.

The Rust That Warns: White Rust as Diagnostic Signal

White rust (zinc hydroxide) on galvanized steel functions as an early warning system—both in reality and potentially in games. When you see white powdery deposits on chain-link fencing or corrugated roofing, the zinc sacrificial coating is being consumed. Once it’s gone, the underlying iron begins rapid oxidation.

In game terms, white rust could signal ‘soft failure’: the structure is still functional but on borrowed time. It’s the metal screaming for help before catastrophic collapse.

Few games exploit this diagnostic potential, but imagine a survival game where recognizing white rust on a bridge warns you to find an alternate route before the iron framework fails. It transforms visual detail into gameplay-relevant intelligence. You’re not just seeing decay—you’re reading a warning written in chemistry.

Pacific Drive comes closest to this idea with its structural integrity system, but even there, rust is generic. What if different rust colors on your car signaled different failure modes? Orange lepidocrocite on body panels (surface corrosion, cosmetic). Yellow-brown akaganeite on the undercarriage (saltwater damage, deep pitting). White deposits on the frame (zinc coating failing, structural compromise imminent).

Suddenly you’re not just “fixing rust”—you’re triaging damage based on chemistry.

When Accuracy Served the Fantasy: Case Studies

This is the central question that emerged from my research: When does accuracy deepen immersion, and when does it just become noise?

Consider these design choices:

Vintage Story chose to use ‘Limonite’ for bog iron. This adds medieval authenticity—it’s what people actually collected to smelt. The accuracy serves the historical simulation fantasy.

Sea of Thieves chose green copper patina (verdigris) for shipwrecks. This reinforces the pirate aesthetic—the visual everyone associates with nautical archaeology. The accuracy serves the fantasy.

Minecraft chose uniform green copper oxidation in all biomes. This keeps the system simple and learnable—you always know what weathered copper will look like. The simplicity serves the creative building fantasy.

Zelda: Breath of the Wild uses rust as a hidden value system—rusty weapons look like junk but can be refined by Rock Octoroks back to powerful equipment. The decay is cosmetic deception, a progression puzzle.

Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom uses rust differently—the purple ‘Gloom’ is a world-wide blight that actively reduces the effectiveness of almost all metal weapons. This isn’t low-oxygen Siderite; it’s narrative corruption. The Depths aren’t just underground—they’re mystically tainted. The fiction serves the story.

All of these work. All of these are correct choices for their respective games.

But I can’t help wondering: what if more games experimented with biome-specific rust? Not to be ‘realistic’—but to create a silent environmental language?

Imagine exploring deeper into Subnautica‘s ocean trenches and noticing the metal supports of your seabase showing different corrosion patterns at different depths. Shallow waters: stable orange lepidocrocite. Mid-depths: darker, more aggressive patterns. Deep ocean: that telltale yellow-brown of chloride pitting, the same akaganeite signature that warns of saltwater’s particular cruelty to metal structures.

“This is different from surface corrosion. This is pressure and salt working together. This is the ocean trying to reclaim my base.”

Would that deepen the simulation? Or would it just be visual clutter?

I honestly don’t know. And that’s what fascinates me.

The Failure Cases: When Rust Became Homework

Understanding why rust mechanics failed in some games is as important as celebrating where they succeeded.

Fallout 3 (2008) and Fallout: New Vegas** (2010) featured comprehensive weapon and armor degradation. Condition affected accuracy, damage, and defense. Repair required duplicate items or high Repair skill. The system was detailed—and many players found it tedious. Forum posts called it ‘micromanagement.’

The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion** (2006) launched with weapon degradation requiring repair hammers and vendor visits. Players found it annoying enough that item durability removal mods became some of the most popular downloads on Nexus.

Fallout 4 (2015) completely removed weapon degradation from the series. Instead: extensive weapon crafting and modification, but zero decay. This represented a significant design pivot—the franchise chose progression systems over maintenance loops.

Fallout 76 (2018) brought degradation back as durability that breaks weapons when empty, repairable at workbenches. The series has wrestled with this mechanic—appearing, disappearing, and returning in different forms—showing how difficult it is to make maintenance feel meaningful rather than punitive.

The player feedback was consistent across multiple iterations: these systems felt like tedious busywork rather than meaningful engagement. But here’s what’s interesting from a design perspective: these games were using rust mechanics as punishment rather than connection.

Compare that to Red Dead Redemption 2 (2018), which launched three years after Fallout 4 removed degradation. RDR2 brought maintenance back—but differently. Cleaning your guns isn’t a chore menu; it’s an animation you watch by the campfire. Arthur’s hands work gun oil into steel. The game makes maintenance feel like care, not obligation.

This distinction matters. When Fallout 3 made you open a menu, select ‘repair,’ click through confirmation dialogs—that was interface friction pretending to be simulation. When Red Dead 2 shows Arthur Morgan’s hands working gun oil into steel, that’s tactile immersion.

The lesson: rust mechanics don’t fail because players hate maintenance. They fail when maintenance feels like clicking through spreadsheets instead of engaging with the world. The games that kept rust—Red Dead 2, Into the Radius, My Summer Car—made it visceral, visible, meaningful. The games that removed it had turned it into homework.

The Invisible Details That Matter

In Red Dead Redemption 2, I began to suspect my guns were rusting faster in the humidity of the Lemoyne swamps than in the arid heat of New Austin. It turns out the game is actually running a hidden ‘Environmental Multiplier’—the engine tracks rain, mud, and water immersion to decide exactly how fast your steel transitions to orange Lepidocrocite.

The game didn’t announce it. It didn’t tutorial it. It just... happened. And when I finally noticed, I felt like I’d discovered something true about the world.

That’s the magic. Not ‘this is realistic,’ but ‘this feels like a world that exists when I’m not looking.’

This is exactly what museums do when we preserve specimens. We collect details that most visitors will never examine. The specific crystal habit of a Goethite specimen from a Kentucky bog. The subtle color difference between urban Brochantite and rural Malachite. The mineral assemblages that record atmospheric composition.

We preserve these details because some visitor, some researcher, someday, will ask the right question. And when they do, the answer will be waiting.

Why does Vintage Story bother to name ‘Limonite’? Why does Sea of Thieves distinguish verdigris from rust? Why does Red Dead 2 track swamp versus desert humidity when most players will never notice?

Because these developers are doing what museums do: preserving questions.

They’re betting that somewhere, a player will wonder: ‘Why is this different?’ And in that moment of curiosity, the world becomes deeper. More real. More worth caring about.

Rust as Possibility

After analyzing all these games, here’s what I learned: games have barely scratched the surface of what rust could mean.

Most games use rust as a timer: ‘This thing is breaking.’ A few games use it as aesthetic: ‘This world is old.’ Even fewer use it as mechanics: ‘This environment is hostile.’

But rust could be detective work. It could be environmental memory. It could be a language as rich as the 12+ minerals I study in the museum.

Imagine a game where you could:

Date ruins by rust color. You discover an abandoned settlement. The iron tools scattered around show red hematite—dry, stable oxidation, suggesting this place has been empty for centuries in an arid climate. But one building has orange lepidocrocite on its hinges—fresh rust, high oxygen, recent disturbance. Someone was here recently.

Track trade routes by patina chemistry. You find three copper coins. One has vivid green malachite (rural carbonate), one has sage brochantite (urban sulfate), one has emerald atacamite (coastal chloride). These coins trace a trade network: countryside → city → harbor.

Diagnose environmental hazards. You enter a cave system. The iron supports near the entrance show normal brown goethite, but deeper in, the metal has turned yellow-brown with aggressive pitting—akaganeite. This cave system connects to the ocean somewhere. There’s chloride in the air. The structure is compromised.

Identify craftsmanship quality. You loot two swords from the same ancient battlefield. One is covered in red hematite—it’s rusted through, barely functional. The other has a lustrous blue-black magnetite coating that’s held for centuries. This was blued steel, made by a master smith who understood controlled oxidation. This sword is still deadly.

The chemistry already exists. The visual language is there. The environmental storytelling potential is enormous.

I don’t know if such a game would succeed. Maybe players don’t want environmental forensics mixed with their adventure. Maybe the cognitive load of learning rust mineralogy would break immersion rather than deepen it.

But I think about the Great Oxidation Event—2.4 billion years ago, when rust first appeared on Earth. Those banded iron formations in ancient rock are planetary memory. They record the moment our atmosphere changed forever. In gaming terms, it was the patch that changed core mechanics—suddenly, free oxygen enabled new mineral formation pathways, created the iron deposits that would later fuel human civilization, and established the redox chemistry we see in every rusted surface today.

When you examine rust in a game, you’re seeing the legacy code from that ancient patch still running. The same electron transfer reactions that turned Archean oceans red with dissolved iron are operating in that corroded car fender.

Rust connects us to deep time—to the moment when Earth’s chemistry changed its operating system. Game developers who understand this history aren’t just placing texture maps; they’re channeling 2.4 billion years of chemical evolution into environmental narrative.

And I think about the Statue of Liberty’s 20-year transformation from bright copper to green patina—a chemical diary of New York’s industrial age, readable to anyone who knows the language.

Rust tells stories. In games, it could tell even more.

The Question We’re Not Asking Yet

Most games ask: ‘What does decay feel like?’ And they answer brilliantly with generic brown rust and clever mechanics.

But somewhere, I think there’s a game waiting to ask: ‘What stories can rust tell?’

And when that game comes, mineralogy will be ready. We’ve been collecting the answers for 200 years.

Love how you're framing rust minerals as environmental storytelling devices rather than just decay mechanics. The malachite vs brochantite distinction for tracking trade routes is genius, basically turning copper patina into a geochemical breadcrumb trail. When I played RDR2 I noticed swamp humidity effects but never connected it to actual lepidocrocite formation kinetics, that hidden enviromental multiplier is doing serious work.