The definition of a mineral has changed over time, and continues to change. The episode dives into what think minerals are today, and how the science is moving forward. The cover image is a kidney stone, which is both a mineral—and not a mineral.

This podcast episode explores the complexities of defining a mineral, which is more complicated than it initially appears. The hosts, Aaron Celestian and Kriss Leftwich, discuss the five generally accepted definitions of a mineral that have come up over the years:

Naturally occurring

Inorganic

Three-dimensionally ordered

Stable at the Earth's surface

Having a defined chemical composition

However, each of these definitions has exceptions and controversies. And at the end of this post, I’ll present a few more definitions that others have come up with.

Naturally Occurring

This definition specifies that minerals must form without human intervention. However, minerals like rowleyite, which forms due to bat guano in a human-made mine, blur this line. The existence of anthropogenic minerals, formed as a result of human activities, further complicates this definition. There is active debate about where to draw the line between natural and human-influenced processes.

Inorganic

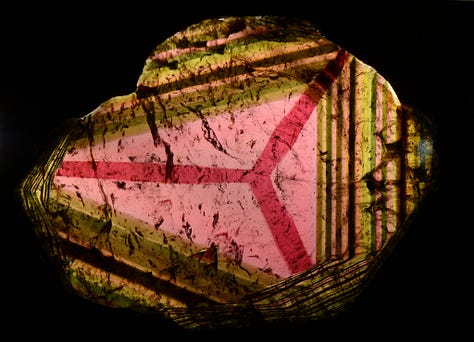

Minerals are traditionally defined as not formed by organic processes. However, this is problematic since organic processes create many minerals. For instance, teeth and pearls are made of the same mineral compounds as rocks but are not classified as minerals. Some minerals, like phoxite, get their oxalate from plants. The definition also raises questions about different types of carbon (organic vs. inorganic) and how they bond. Even limestone, formed by reef-building organisms, is considered a mineral.

Three-Dimensionally Ordered

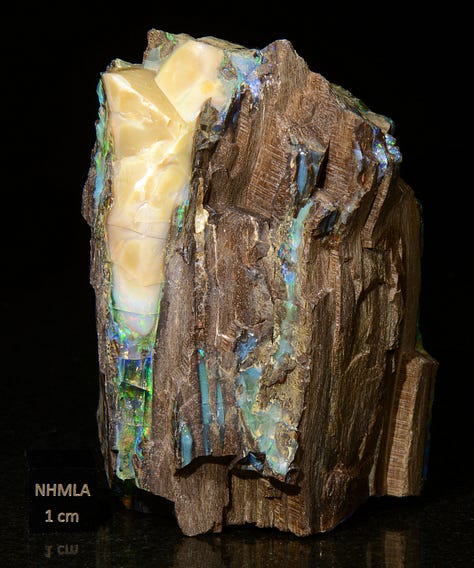

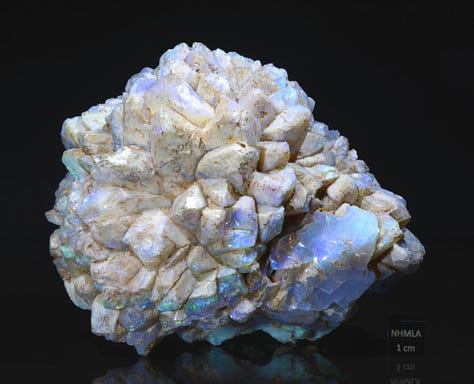

This refers to the repeating patterns of atoms in a crystal. However, some substances like opals, called mineraloids, have order on the scale of light rather than on the atomic scale (photonic crystals). Also, some opals have no crystal structure, while others have some crystallinity in the form of the minerals cristobalite and tridymite. Other examples of materials that challenge this definition include graphene and graphite, which are ordered in two dimensions, and nanominerals like ferrihydrite, which has very short-range ordering. X-ray diffraction is traditionally used to quantify crystallinity, but some materials don't produce clear patterns.

Stable at the Earth's Surface

This definition is also controversial. Diamond is a mineral, but it is not stable at the Earth’s surface. Ice is considered a mineral, though its stability varies by location on Earth. Additionally, minerals like ikkaite are only stable under specific conditions and can melt easily. Mirabilite readily converted to thenardite when temperatures warm above freezing. To further complicate things, there are minerals on other planets, so there is a question of whether a crystalline material found on elsewhere in our solar system but not on Earth should be considered a mineral—which is clearly ridiculous to not consider them minerals.

Defined Chemical Composition

The definition of a defined chemical composition depends on who is studying the mineral. Some minerals, like tourmaline and hornblende, have highly variable compositions, incorporating many different elements. Other minerals, like forsterite and fayalite (both part of the olivine group), can have varying amounts of iron and magnesium. There are also cases, like high magnesium calcite, which is not classified as a separate mineral despite having different properties. Mineralogists who focus on small variations are called "splitters," while those who group minerals together are called "lumpers". Calling someone a lumper or splitter is not necessarily a comment to give (so it’s not good idea to just go around calling people these names). A committee governs what defines a mineral, and they are constantly changing nomenclature as the science evolves.

Evolution of Minerals

We also touch on the idea of mineral evolution, which examines how minerals have changed and diversified over time, influenced by life. This concept challenges the definition of minerals as strictly inorganic. The number of minerals present on a planet can indicate whether life is present. The hosts mentioned that they plan to discuss mineral evolution further in a future episode.

Mineral definitions from other sources

From Donald Peck via Mindat.org

A mineral is a chemical element or compound that:

Has a more-or-less constant composition.

Is usually a solid with an ordered three dimensional array of ions and molecules in its crystal structure.

Is formed by natural geologic processes and without human or other biologic intervention.

Is not a mixture of two or more blended substances.

From the International Mineralogical Association

The IMA Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification has a document that is 13 pages long where they discuss what a mineral is and how to classify it. It was published in 1998, and it is still referenced on their official website (I accessed it on December 19, 2024). I’m going to attempt to summarize the paper below:

The Canadian Mineralogist paper defines a mineral as a naturally occurring solid formed by geological processes with a well-defined chemical composition and crystallographic properties. A new mineral species must have a substantially different composition, typically with a different chemical component predominating at least one structural site compared to existing minerals. It also needs distinct crystallographic properties, with polymorphs considered separate species only if their structures are topologically different. The definition excludes human-made substances, though some biogenic substances and amorphous materials can qualify under specific conditions. The paper addresses complex cases including polytypes, regular intergrowths, and solid solutions, noting that only end members of a continuous binary solid-solution series are considered distinct species, and that a 50% rule is applied to determine which elements define the mineral in multiple solid solution series. Essentially, they present guidelines for classifying minerals, emphasizing that each case must be judged on its own merits.