The Zeolite Paradox

Why Video Games Ignore One of Industry's Most Important Minerals

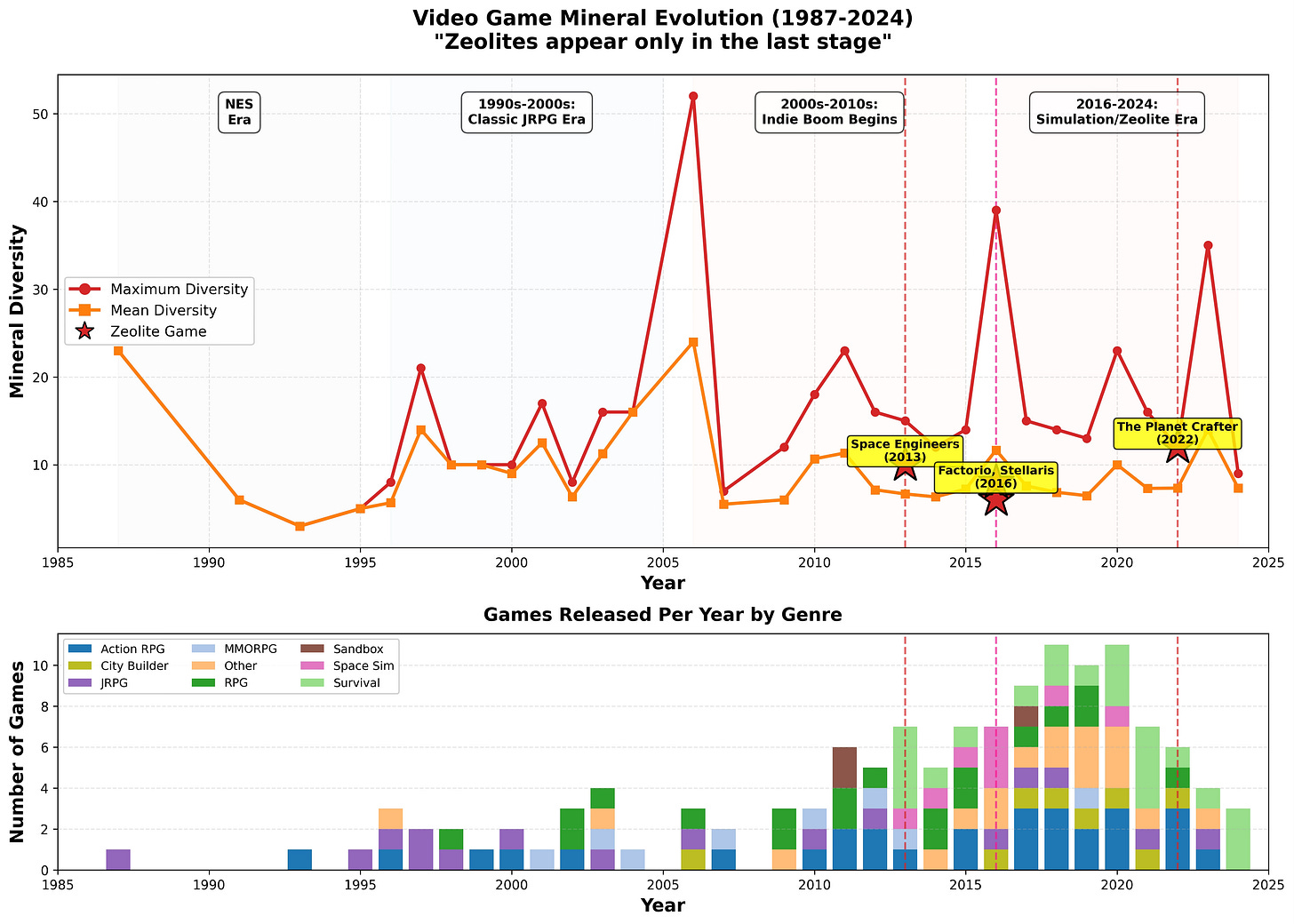

I analyzed 161 games and revealed a 53-year cultural lag between industrial importance and digital representation.

I‘ve spent the last few months obsessively cataloging minerals in video games. Not because I’m a completionist trying to 100% every RPG, but because I noticed something strange. In all my years of gaming—from Final Fantasy to Skyrim, from Minecraft to Stardew Valley—I’d never encountered a zeolite.

This might not sound shocking. Maybe you’re thinking, “So what? I’ve never heard of zeolites either.” But here’s the thing: you interact with zeolites every single day. They’re in your laundry detergent, your cat litter, your water filter. The petroleum that became the plastic in your phone passed through zeolite catalysts. But that’s just the everyday stuff. These microporous aluminosilicate minerals are at the cutting edge of solving civilization-scale challenges: researchers are engineering zeolite-like materials to deliver anti-cancer drugs directly to tumor cells, to extract lithium from wastewater for battery production, to capture CO₂ from industrial emissions. The global zeolite market is worth over $30+ billion annually and growing. These aren’t niche laboratory curiosities—they’re essential infrastructure of modern life, materials that quite literally help power, clean, and potentially save the world.

Yet in the vast digital worlds we’ve created—universes where we mine asteroids, craft magical weapons, and terraform entire planets—zeolites are almost completely absent.

I wanted to know why.

The digital worlds we create reflect the real world we value.

The Census Begins

I started simply enough. I made a spreadsheet. On one axis: every game I could think of with a mining or crafting system. On the other: what minerals appeared in each game.

The results were immediate and striking. Diamonds, rubies, emeralds, sapphires—these appeared in game after game. Even obscure gemstones like sunstone and citrine showed up regularly. Gold, silver, copper, iron—the classic metals of human civilization were everywhere. Some games got creative with fictional materials: Minecraft’s redstone, Skyrim’s ebony, Terraria’s chlorophyte.

But zeolites? In my initial survey of 100+ games, I found exactly zero.

This seemed impossible. I expanded my search, diving deep into simulation games, space exploration titles, hard sci-fi survival games—genres that pride themselves on scientific accuracy. I scoured wikis, studied crafting tables, read through material lists for dozens of games.

After examining 161 games spanning from 1987 to 2025, I found zeolites in exactly four games. Four. Out of 161.

That’s a 2.5% appearance rate for one of the most industrially critical minerals of the past 60 years.

What Are Zeolites, Anyway?

Before we dig deeper into this paradox, let me explain what makes zeolites special—because if games don’t represent them, most people never learn about them at all.

Zeolites are crystalline minerals with a honeycomb-like structure full of microscopic pores. Think of them as molecular sieves: their pores are perfectly sized to trap specific molecules while letting others either pass through or bounce off the crystal surface. This makes them extraordinary for:

Catalytic cracking in oil refineries (converting crude oil into gasoline)

Water purification (removing heavy metals and radioactive ions)

Detergents (softening water by exchanging calcium for sodium)

Gas separation (pulling CO₂ out of industrial emissions)

Agriculture (slowly releasing fertilizers)

The catalytic cracking application alone is staggering. According to industry estimates, zeolite catalysts are involved in petroleum processes generating over $10 billion annually. When you fill up your car with gas, there’s a good chance zeolites helped make it possible.

Natural zeolites have been known since 1756 (Swedish mineralogist Axel Fredrik Cronstedt coined the name from Greek words meaning “boiling stone”). But their industrial revolution began in earnest in the 1960s when chemists learned to synthesize zeolites with designer pore structures. By 1970, zeolite catalysts had transformed the petroleum industry. By the 1980s, they were in your laundry detergent.

Today, there are over 250 known zeolite framework types, both natural and synthetic. They’re traded globally. They’re the subject of thousands of scientific papers annually. They’re essential infrastructure of modern life.

So why don’t they exist in our games?

The Four Exceptions

Let me tell you about the four games that broke the pattern.

Space Engineers (2013) was first. This hardcore space construction simulator lets you build ships and stations from realistic materials. In the modding community—particularly among players seeking maximum realism—zeolites appear as the base game doesn’t include them. While the game focuses on ores like Iron and Uranium, the community frequently discusses real-world materials like zeolites—which NASA uses for air filtration—as the type of specialty resource they want to see added for maximum immersion, but the fact that dedicated players added them is telling.

Factorio (2016) and Stellaris (2016) followed similar paths. Factorio, an ultimate factory-building game, includes zeolites in its popular “Space Age” expansion for chemical processing chains. Stellaris, the grand strategy space game, features zeolite deposits as planetary modifiers—but they’re background flavor, barely noticeable compared to dramatic resources like “Zro” or “Dark Matter.”

It wasn’t until The Planet Crafter (2022) that zeolites appeared in a base game without mods. This terraforming simulator features zeolites as a mineable resource used in advanced atmospheric processors—exactly their real-world application in gas separation and is a vital late-game mineral.

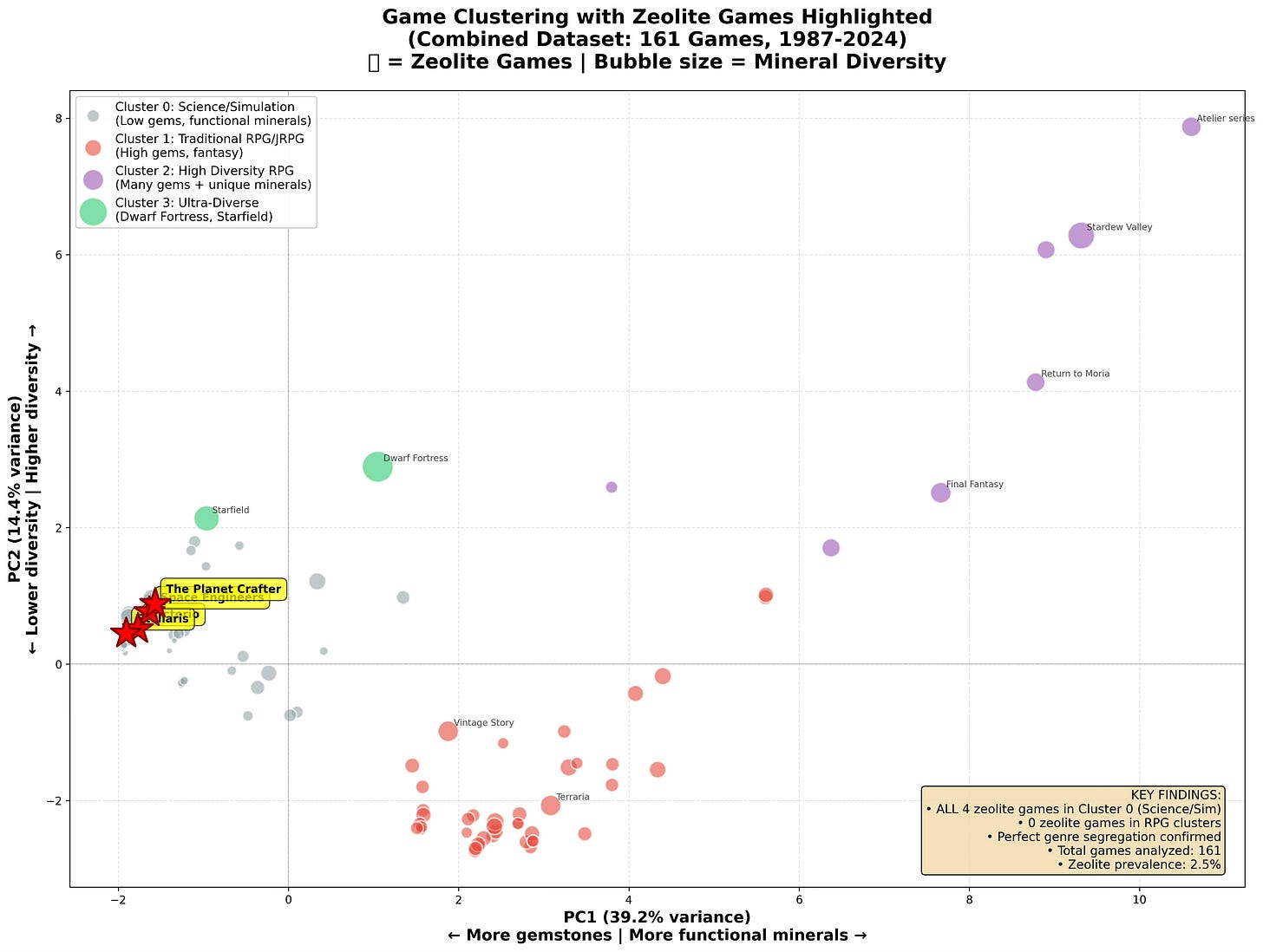

Notice a pattern? All four games are simulation-focused titles emphasizing scientific accuracy. All four involve space, engineering, or industrial processes. And critically: all four have zero traditional gemstones.

Not a single ruby. Not one emerald. No diamonds for jewelry, no sapphires for magic rings in any of the base version of these games.

The Great Divide

This is where things get interesting. I didn’t just catalog which games had zeolites—I tried to record everything. Every gemstone, every mineral, every ore. And I suspected there was a pattern hiding in the data, something beyond simple observation.

To test my hypothesis, I needed to move from intuition to statistical rigor. I performed principal component analysis on the complete dataset—a technique that reveals hidden structure in complex data by identifying the fundamental axes along which things vary. What I found was remarkable: the games didn’t exist on a spectrum. They clustered into four distinct groups, separated almost perfectly by their material philosophies.

Cluster 0: Science/Simulation (109 games, 67.7%)

Average standard gemstones: 0.44

Average unique minerals: 5.71

Zeolite games: 4 (100% of all zeolite games)

Cluster 1: Traditional RPG/JRPG (43 games, 26.7%)

Average standard gemstones: 6.47

Average unique minerals: 4.95

Zeolite games: 0

Cluster 2: High Diversity RPG (7 games, 4.3%)

Average standard gemstones: 11.86

Average unique minerals: 9.00

Zeolite games: 0

Cluster 3: Ultra-Diverse (2 games: Dwarf Fortress, Starfield)

Average standard gemstones: 1.00

Average unique minerals: 42.50

Zeolite games: 0

The segregation is almost perfect. Games fall into two distinct categories: those with lots of gemstones and no zeolites, and those with functional minerals that might include zeolites. The correlation isn’t just strong—it’s nearly absolute.

I call this the Function vs. Folklore divide.

Folklore Wins

Let me illustrate this with two games released the same year: Final Fantasy (1987) and... well, actually, that’s the problem. There was no scientifically accurate mining game in 1987. But Final Fantasy established a template that would echo through gaming for decades.

Final Fantasy’s mineral system includes: ruby, diamond, opal, topaz, sapphire, emerald, and more—12 standard gemstones in total. It also features “cinnabar” (real: mercury ore), “pyrite” (real: iron sulfide), and various fantasy minerals. It’s a maximalist gemstone collection that looks like someone raided a jewelry store and a fantasy novel simultaneously.

Fast forward to 2018’s Octopath Traveler—a spiritual successor to classic JRPGs (Japanese Role-Playing Games). The game features 10 standard gemstones used to create “soulstones” that boost character stats. Each gemstone has associated lore, a specific power, a place in the game’s metaphysical system.

Now compare that to Vintage Story (2020), a hardcore survival game aimed at players who think Minecraft is too arcade-y. Vintage Story features 18 real minerals with scientifically accurate names: cassiterite (tin ore), galena (lead ore), sphalerite (zinc ore), magnetite and limonite (iron ores).

No zeolites, but the game’s philosophy is clear: function over folklore. These minerals exist not because they sound cool or have ancient mystical properties, but because they’re what you’d actually find while mining. The game trusts players to learn terms like “sphalerite” rather than simplifying to “zinc ore.”

Here’s what I realized: gemstones have narrative power. When a fantasy novel mentions “a ruby the size of a dragon’s eye” or “a sapphire that glows with elven magic,” readers immediately understand the stakes. We have cultural associations with gemstones going back millennia. They represent wealth, power, beauty, magic.

Zeolites have none of that. They’re beige. They’re powdery. Their name sounds vaguely medical or scientific. When I tell people about zeolites, their eyes glaze over—then light up when I mention they’re in cat litter. Cat litter! Not exactly the stuff of legends.

This isn't just a gaming problem—it's a science communication problem. If the average person never encounters zeolites in media, how would they know these materials exist? How would they appreciate their importance?

The 53-Year Cultural Lag

But the absence of zeolites in games isn’t just about narrative appeal. It reveals something deeper: a troubling gap between industrial importance and cultural awareness—and games both reflect and perpetuate this knowledge gap.

Zeolites became commercially critical in the 1960s with catalytic cracking applications. By the 1970s, they were revolutionizing petroleum refining. By the 1980s, they were in consumer products. Yet the first video game appearance wasn’t until 2013—a gap of over 53 years from industrial adoption to digital representation.

For comparison:

Uranium was weaponized in 1945, appeared in games by the 1980s (35-year lag)

Silicon became the basis of computing in the 1960s, was referenced in games by the 1980s (20-year lag)

Diamonds have been prized for jewelry since antiquity, appeared in early RPGs immediately (minimal lag)

The pattern is clear: materials with cultural narratives (uranium = atomic power, diamonds = wealth) enter games quickly. Materials with purely industrial importance lag significantly. And materials that are both industrially critical and culturally invisible (like zeolites) might not appear at all.

This isn’t just a gaming problem—it’s a science communication problem. If the average person never encounters zeolites in media, how would they know these materials exist? How would they appreciate their importance? And more critically: how would the next generation of materials scientists discover their passion for the field if the materials that power civilization remain invisible in the worlds we build for entertainment and learning?

The Mythril Effect

Here’s what makes this even more fascinating: while zeolites are nearly absent, entirely fictional minerals appear constantly.

Mythril (or mithril)—the legendary metal from Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings—appears in at least 7 games in my dataset:

Final Fantasy series

Dragon Quest Builders (both games)

Kingdom Hearts

Craftopia

And more

Orichalcum, the mythical Atlantean metal mentioned by Plato, appears in at least 6 games:

Kingdom Hearts

Final Fantasy

Dragon Quest

Craftopia

Harvest Moon

Star Ocean

These materials don’t exist. They never existed. Tolkien invented mithril in 1954 as “true silver.” Orichalcum was a legendary metal even in ancient Greece—possibly brass, possibly fiction, definitely not a real element.

Yet they appear in more games than zeolites—materials that are provably real, economically critical, and sitting in your laundry room right now.

Why? Because mythril and orichalcum have stories. Mythril is “stronger than steel, lighter than silk, used by the dwarves of Moria.” That’s a narrative. That’s evocative. “Zeolite: microporous aluminosilicate with exceptional ion-exchange properties” is... technically accurate but dramatically inert.

Community-Driven Realism

The Stellaris case deserves special attention because it reveals something important about how scientific accuracy enters games.

In vanilla Stellaris, zeolites exist as a minor planetary feature. You might find “Zeolite Deposits” that provide a small bonus to mining districts or trade value. The game describes them accurately—used for “high-tech filtration and chemical processing”—but they’re forgettable compared to exotic resources like “Living Metal” or “Zro.”

Then the modding community stepped in. Popular mods like “Real Space” and “Planetary Diversity” elevate zeolites to a distinct, mineable resource with specific industrial applications. Players who want more complex chemical production chains asked for zeolites specifically.

This pattern repeats: Space Engineers’ zeolites are modded. Factorio’s are modded. When a subset of players demands scientific accuracy, they don’t ask for more gemstones—they ask for realistic industrial minerals.

This is science communication happening from the ground up. Enthusiast players are essentially volunteering as unpaid educators, filling the “realism gap” that commercial game design leaves behind. They’re translating industrial chemistry into game mechanics, making catalytic cracking and ion exchange fun.

But why is this labor necessary? Why don’t commercial games include these materials by default?

Design Philosophy and Market Forces

I’ve corresponded with several indie game developers about mineral selection. The consensus is clear: gemstones are safer.

When you’re designing a fantasy RPG, you have two options:

Option A: Use emeralds, rubies, diamonds, sapphires

Players immediately understand their value

Clear visual identity (green, red, white, blue)

Established hierarchy (everyone knows diamonds > rubies > emeralds in most systems)

Zero explanation needed

Option B: Use zeolites, feldspars, perovskites

Players: “What’s a zeolite?”

No inherent visual identity

No obvious hierarchy

Requires explanation, possibly a wiki entry

Option A lets you ship on time. Option B requires player education.

For simulation games targeting hardcore enthusiasts, the calculus is different. These players want to learn. They enjoy the Wikipedia rabbit hole. A Factorio player who spends 100 hours optimizing an oil refinery will absolutely read about catalytic cracking. A Vintage Story player will learn the difference between magnetite and hematite because the smelting temperatures are different.

But these are niche markets. The mass-market RPG—your Final Fantasy, your Skyrim—must appeal to millions of players, most of whom just want to stab dragons and collect loot. Explaining zeolites doesn’t serve that goal.

So we get gemstones. Always gemstones.

What We Lose

This might seem like a trivial observation. Who cares if games use rubies instead of zeolites? They’re just games, right?

But games are now a $200+ billion industry—larger than movies and music combined. Millions of people, especially young people, spend thousands of hours in virtual worlds. These worlds teach systems thinking, resource management, economic principles. They shape how we understand materials, scarcity, value.

When every game uses the same gemstone hierarchy, we reinforce a pre-industrial understanding of material value. We teach that precious = rare + beautiful. We don’t teach that precious might mean “enables catalytic cracking” or “removes heavy metals from groundwater.”

I grew up playing JRPGs where rubies were the ultimate crafting material. I learned that diamonds were valuable, emeralds were powerful, opals were mystical. I learned nothing about the materials that actually power modern civilization.

This matters for science literacy. Studies consistently show that Americans can name far more gemstones than industrially important minerals. We’ve culturally prioritized sparkly rocks over functional materials.

Games could help fix this—but only if they choose to.

The Four That Tried

Let me return to those four zeolite games, because they represent something important.

The Planet Crafter deserves special recognition. This is the only game where zeolites are a core, unavoidable resource in the base game. You need them to terraform Mars-like planets, using them for atmospheric processing and chemical separation—their actual real-world applications.

The game trusts players to engage with realistic materials. Your progression path involves mining not just “gems” but specific industrial minerals: zeolites, titanium, uranium, osmium, iridium. The game doesn’t dumb this down. It doesn’t rename zeolite to “filter stone” or “air crystal.”

And players love it. The game has “Very Positive” reviews on Steam, with players specifically praising the realistic resource system. Turns out that if you build a game around science, players interested in science will show up.

Factorio takes a different approach. The base game focuses on factory optimization without getting bogged down in chemical realism. But the community-created “Space Exploration” mod adds zeolites specifically for players who want deeper industrial chains. It’s opt-in realism.

Stellaris shows what happens when scientific accuracy is flavor rather than function. Zeolites exist in the lore—they’re mentioned in planet descriptions, they provide minor bonuses—but they’re not important. They’re the mineral equivalent of a footnote.

Space Engineers, meanwhile, demonstrates how modding communities self-organize around scientific accuracy. The base game provides realistic construction and engineering, and players extend that realism to materials.

These four games prove it’s possible. They prove players will engage with scientifically accurate materials if given the chance. They prove zeolites can work in games. They’re just really, really lonely doing it.

The Flat Line Problem

Here’s the most damning evidence: the average mineral diversity in games hasn’t increased in 37 years.

Look at the data. From 1987 to 2024, while games evolved from 8-bit sprites to photorealistic graphics, from single-player cartridges to massive online worlds, from kilobytes to terabytes—the average number of minerals in games remained essentially flat. Around 8-12 materials. .

Final Fantasy in 1987 had 23 minerals. The average game that year had about 14. In 2024? The average is still around 10. We’ve mastered ray tracing, procedural generation, and physics engines that simulate individual grass blades. But we’re still collecting the same rubies and diamonds.

The spikes you see—Dwarf Fortress’s 52 minerals in 2006, Stardew Valley’s 39 in 2016—aren’t evidence of progress. They’re exceptions that prove the rule. Outliers created by individual developers who chose to break from convention. The industry as a whole hasn’t budged.

This isn’t about technological limitation. Modern games can track thousands of variables, render billions of polygons, simulate complex chemistry. We could include zeolites, rare earth elements, industrial minerals. We have the capacity. We lack the will.

The flat trendline reveals something uncomfortable: cultural lock-in. Somewhere around 1987, games established a template—gemstones good, industrial minerals invisible—and we’ve been copying it ever since. Not because it’s optimal. Not because players demand it. But because it’s what games are supposed to have.

This is the feedback loop in action. Developers learn what materials matter from the games they played. Those games taught them rubies and emeralds. So they make games with rubies and emeralds. The next generation learns the same lesson. The cycle continues.

Breaking this cycle requires conscious choice. It requires developers to ask: “Why are we using these materials? What are we teaching players about value? What opportunities are we missing?”

The Broader Pattern

But zeolites are just the beginning. They’re my particular research focus—I spend my professional life studying microporous minerals and their atom and molecule sieving properties—but they’re also a proxy for a much larger issue. My dataset revealed dozens of industrially critical materials that are nearly absent from games:

Rare earth elements (neodymium, dysprosium, europium): Essential for electronics, magnets, and batteries. Appearance rate: ~5%

Lithium: Powers every smartphone and electric vehicle. Appears in 12% of games, usually sci-fi

Bauxite/Aluminum: Most abundant metal in Earth’s crust, third most abundant element. Surprisingly rare in games

Tungsten: Highest melting point of any metal, critical for tooling. Appears in ~15% of games

Phosphates: Essential for all life, the basis of fertilizers. Almost never appear

Meanwhile, fictional or pre-industrial materials dominate:

Standard gemstones (ruby, sapphire, emerald, diamond): 60%+ appearance rate

Mythril/Orichalcum: 7-8% appearance (despite not existing)

Gold/Silver: Near-universal, despite limited modern industrial use

“Magic crystals” or “mana stones”: Appear in 30%+ of fantasy games

The pattern is consistent across every functional material category: narrative appeal > industrial importance.

This reflects something fundamental about what our society perceives as valuable and what we choose to celebrate in our cultural products. When we create digital worlds, we populate them with the materials of pre-industrial fantasy—gemstones, precious metals, mythical substances—rather than the materials that genuinely power modern civilization. We’re building futures out of the past’s understanding of value.

A Proposal

I’m not suggesting every game needs zeolites. That would be absurd. Final Fantasy should keep its rubies and crystals—they serve the fantasy narrative perfectly.

But what if simulation games, space games, and “realistic” survival games made a conscious effort to include scientifically accurate materials? What if developers partnered with geologists and materials scientists the way they partner with military consultants for shooters?

Imagine a mining game where you learn to recognize zeolite’s crystal structure. Where you understand why certain deposits are valuable for catalysis versus ion exchange. Where the progression system mirrors actual industrial applications.

We do this for other sciences. Kerbal Space Program taught a generation of players about orbital mechanics. Factorio teaches systems thinking and industrial engineering. Civilization teaches (simplified) history and economics.

Why not materials science?

The Educational Opportunity

Here’s what gets me most excited: games could be the perfect medium for teaching about materials.

Consider what games do well:

Visual learning: You can see, rotate, and interact with 3D mineral structures

Systems thinking: Understanding how materials fit into larger industrial processes

Progression: Learning complexity gradually, from simple ores to advanced materials

Application: Using materials in context, not just memorizing facts

Motivation: Players want to learn because it helps them succeed

A well-designed mining game could teach zeolite chemistry better than any textbook. You’d learn by doing—by building filtration systems, by optimizing catalytic processes, by choosing the right material for each application.

Some games are already doing this. Vintage Story’s geology is so detailed that players have created their own guides to ore formation and prospecting. Oxygen Not Included players learn about thermodynamics and gas laws through gameplay. These games prove educational depth and fun aren’t mutually exclusive.

The Cultural Feedback Loop

But there’s a deeper issue at play. Games don’t exist in isolation—they both reflect and reinforce cultural values.

When games consistently portray gemstones as the most valuable materials, they strengthen existing biases. Players learn (implicitly) that shiny = important, industrial = boring. This makes them less likely to pursue careers in materials science, less likely to appreciate infrastructure, less likely to understand modern technology.

Then those players grow up and some become game developers. And they make games with gemstones, because that’s what they learned games should have. The cycle continues.

Breaking this cycle requires conscious effort. It requires developers to say: “Yes, zeolites aren’t as immediately appealing as rubies, but they’re important, and we’re going to make them interesting.”

The Planet Crafter did this. It’s possible.

My Hope

After months of research, thousands of spreadsheet cells, and more hours in mining menus than I care to admit, I’ve reached a simple conclusion:

The digital worlds we create reflect the real world we value.

Right now, our games tell us that diamonds matter more than catalysts, that rubies are more important than zeolites, that magic crystals deserve more attention than the materials that actually power civilization.

We can do better.

I’m not calling for a revolution in game design. I’m not demanding every fantasy RPG swap its gemstones for industrial minerals. But I am suggesting that games—especially simulation games claiming to be realistic—have an opportunity and perhaps a responsibility to represent the materials that genuinely matter.

Zeolites won’t make a game fun by themselves. But they’re a starting point for a conversation about what we choose to include in our digital worlds, and why.

Because here’s the thing: every time a game developer sits down to design a crafting system, they make a choice. They decide what materials exist in their universe. They decide what players will spend hours collecting, learning about, and valuing.

Those choices echo. They shape how millions of players understand material value, industrial importance, and scientific literacy.

Right now, those choices are leaving zeolites behind. And in doing so, they’re leaving behind an opportunity to make the invisible infrastructure of modern life visible, tangible, and maybe even exciting.

After all, what’s more magical: a ruby that sparkles, or a microporous crystal that can pluck CO₂ molecules out of the air, one at a time, helping to save the planet?

I know which one I’d rather have in my inventory.

Have you encountered zeolites in a game I missed? Found other industrially important materials that games ignore? I’d love to hear about it.

This is such a brilliant observation about how games reflect cultural biases toward shiny over functional! I've been playing factory sims for years and never really thought about why we always mine the same old gems. Your point about the 53-year lag is defintely making me rethink what I teach my kids about valuable materials when we play Minecraft togther. Would love to see zeolites in the next survival crafting game!